Table of Contents

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: The Era of AI: Now and Tomorrow

Part 3: How AI is Transforming Higher Education

Part 4: The Future of Work

In early 2023, as the job market reached normalcy following the pandemic, we got a surprise.

ChatGPT became the fastest-growing consumer application in history.

As a McKinsey report on the future of work notes, AI experts knew the natural language capabilities demonstrated by ChatGPT, and generative AI like it, was coming. But not until 2028 at the earliest.

So, once again, companies, employees, and educators found themselves at an inflection point.

The era of AI had arrived.

While automation sounds good to business leaders whose companies benefit from increased productivity, for individuals, it can cause anxiety.

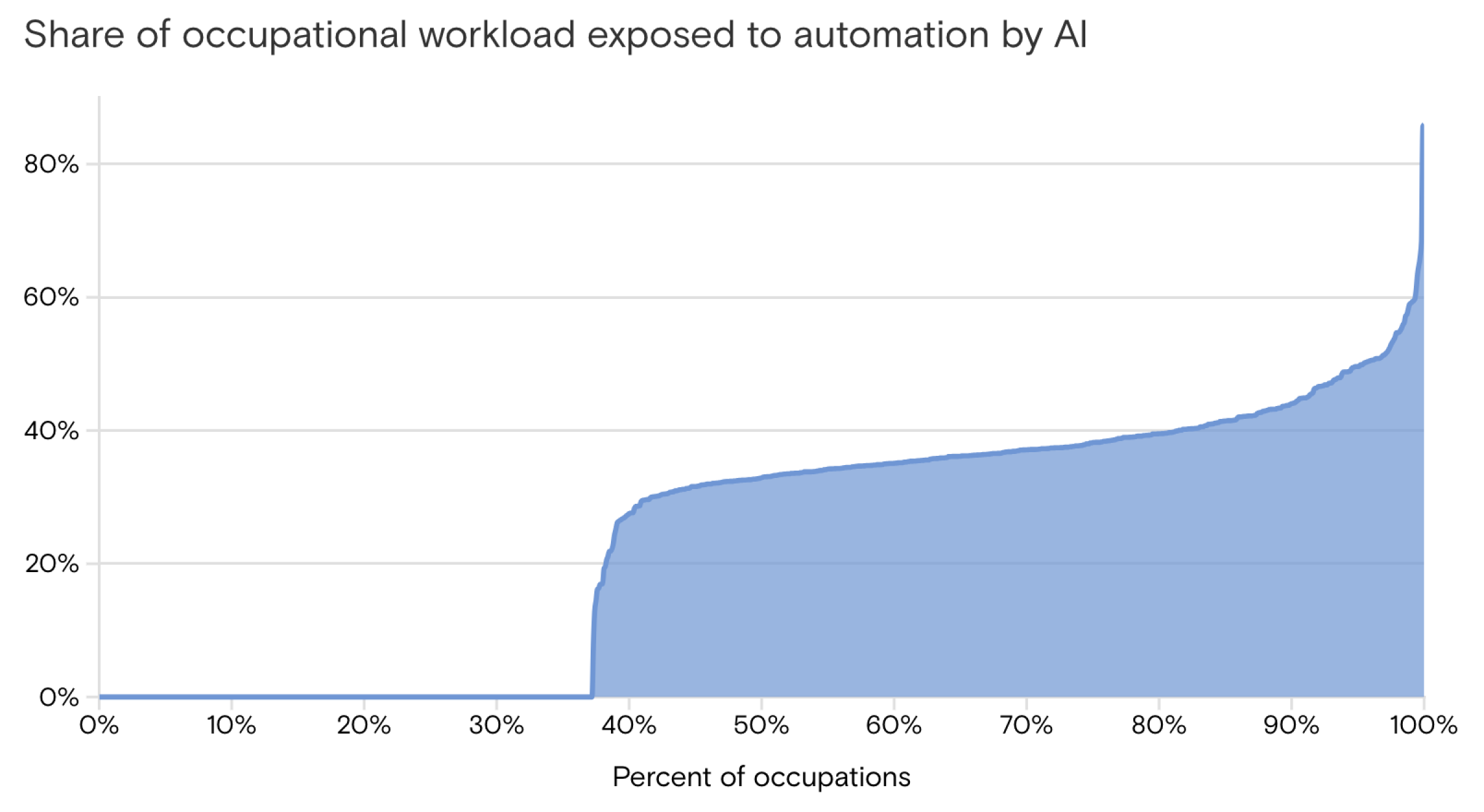

Roughly two-thirds of U.S. occupations are exposed to some degree of automation by AI, according to Goldman Sachs Research.

The good news is that “most jobs and industries are only partially exposed to automation and are thus more likely to be complemented rather than substituted by AI.”

Additionally, “higher levels of educational attainment remain strongly positively correlated with being in less automatable roles,” according to McKinsey.

Two thirds of occupations could be partially automated by AI

Source: Goldman Sachs Research

How AI Is Changing Jobs

The jobs that took the biggest hits during the pandemic are the ones that will suffer the most as automation and generative AI gain hold.

Those include low-wage, customer-facing jobs like retail and food services. Customer service and administrative office jobs are more at risk as well. AI chatbots are predicted to replace many customer service representatives. AI-powered document management is already taking over routine office work. Not all productivity gains from AI will eliminate office jobs. But roles will certainly be altered.

Overall, generative AI is expected to give workers back 30 percent of hours they can dedicate to higher level work. This has the potential to bring greater satisfaction to people whose jobs have become more administrative as we’ve strived to digitize our economy.

Doctors, for example, may have more time to talk with their patients instead of filling out online forms.

Here are a few other examples of what jobs will look like with generative AI. In some cases, like lawyers, it’s already happening.

- Lawyers are being freed up to think through how to apply case law instead of spending hours and hours searching through relevant precedents. Generative AI is doing the work for them.

- Civil engineers and architects are using generative AI to accelerate the design process. For example, AI accounts for building codes, reducing errors and rework, particularly for complex mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems.

- Managers can rely on automation for mundane administrative and reporting tasks and use the time saved to provide more one-on-one coaching.

- Researchers are reducing the time they spend sorting and synthesizing data or conducting literature searches of existing studies, spending more time on original contributions and speeding research projects.

- Teachers are using generative AI to grade tests and flesh out lesson plans and focus more of their energy on interacting with students.

- Designers, writers, and other members of creative fields are benefiting from generative AI. Intelligent software is creating storyboards, first drafts, and other artifacts. Creative professionals continue to provide the ideas and shape what tools produce (via prompt engineering, for example) and apply the artistic judgment AI might just never be able to replicate.

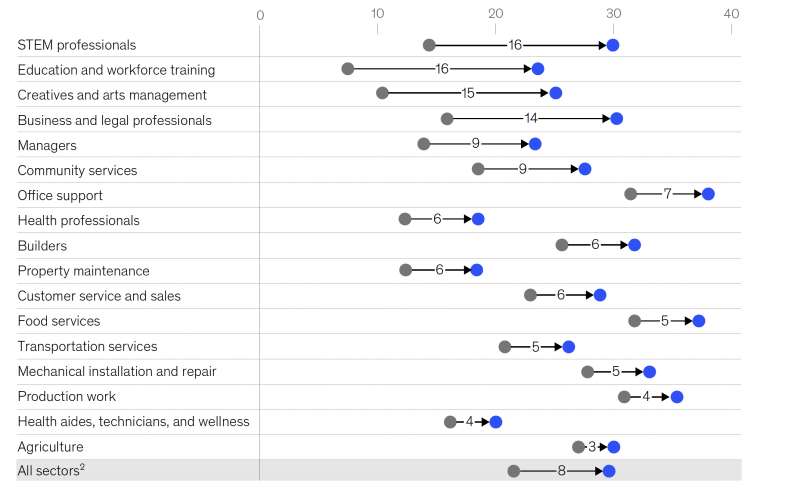

While AI is reshaping many roles, it is increasing demand for others.

Jobs in STEM fields are estimated to grow by 23 percent by 2030, for example. The top-growing occupations include software developers, computer systems analysts, and data scientists. Some of this growth is related to the deployment of automation systems themselves.

With generative AI added to the picture, 30% of hours worked today could be automated by 2030

Source: McKinsey Global Institute

Skill Building

It’s not surprising that higher ed will need to help students — in all disciplines — develop the technological skills required to thrive in an increasingly AI-enhanced labor market.

What might be surprising is the other skills predicted to be most in demand by 2030: social and emotional.

As illustrated in how doctors’ and managers’ jobs will involve more human interaction as AI takes over mechanical tasks, the professionals that will succeed will be those who can do things bots can’t.

Skills like emotional intelligence, “reading the room,” collaborating, constructive criticism, problem-solving, compassionate leadership, time management, and so many of the characteristics of the people we love to work with will be even more essential.

Workplaces continue to get more diverse — in ages and ethnic and cultural backgrounds, for example — making it necessary for people with different life experiences to work together towards common goals.

It’s these “soft skills” that higher ed has traditionally been exceptional at helping students develop not just for a job interview but as an intrinsic, lifelong capacity.

Technical, emotional, and social skills will also strengthen students’ adaptability.

After all, change is and will be the most reliable constant in the coming decades.

A study by economist David Autor, for example, found that “60% of today’s workers are employed in occupations that didn’t exist in 1940. This implies that more than 85% of employment growth over the last 80 years is explained by the technology-driven creation of new positions.”

“60% of today’s workers are employed in occupations that didn’t exist in 1940. This implies that more than 85% of employment growth over the last 80 years is explained by the technology-driven creation of new positions.” --Economist David Autor

The Future of Work in Higher Ed

AI offers enormous opportunities to reduce the tedious administrative activities that bog down employees and increases operational costs.

When thinking about how to staff for the future of higher ed, there’s a natural inclination to race to LinkedIn and update job postings to include AI experience.

What many experts suggest is that the transition to the era of AI is a call for employers to hire for capacity to learn and adapt to new technologies.

“Employers will need to hire for skills and competencies rather than credentials, recruit from overlooked populations (such as rural workers and people with disabilities), and deliver training that keeps pace with their evolving needs,” writes McKinsey.

They note that the companies with the best bottom lines are the ones with the strongest organizational health, offer the most coaching and training, and provide pathways for internal advancement.

In short, addressing the staffing problems in higher ed may involve cultivating the talent you already have. Employees who feel like their employers are investing in them are more likely to invest their time in their employers.